Amid our busy life, sleep is often one of the first things we deprioritize, for example, by reducing amount of sleep each night, sleeping too late at night, or having poor sleep habits.

Sleep affects so many aspects of our health including immune function, cognitive function, metabolic function, digestive function, hormonal balance, and weight management. Sleep also influences our risks of developing certain chronic diseases including diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, liver disease, gastrointestinal (GI) disorders/diseases, cancers, Alzheimer’s disease/dementia, and mental illness.

Therefore, the importance of sleep should not be overlooked.

Sleep issues are prevalent in our modern society, including difficulty falling asleep or insomnia, difficulty staying asleep, poor sleep quality, difficult getting up in the morning and waking up feeling unrested.

In this blog, I share some of the obvious and not-so-obvious contributing factors to sleep issues and provide evidence-based tips for improving your sleep so that you can take charge of your health.

For a quick summary of the tips to improve sleep, you can go directly to the Summary section.

Topic List

Chronic Diseases and Conditions

Factors Contributing to Sleep Issues

Stress and Cortisol Dysregulation

Poor Sleep and Lifestyle Habits

Summary

The wide-ranging and detrimental effects of sleep deprivation and sleep disturbance on our physical and mental health are first described in the section How Sleep Affects Our Health.

As described in the section Factors Contributing to Sleep Issues, sleep issues not only can be due to poor sleep habits but can also be due to some deeply rooted health issues that we may overlook including chronic mental/emotional stress and physical/physiological stress, GI/gut dysfunction, unhealthy gut flora, and chronic parasite infections.

To improve sleep, factors contributing to sleep issues should be addressed, as summarized below (for more details, see Tips for Better Sleep).

How Sleep Affects Our Health?

Sleep, alongside with food, water and air, is an essential biological requirement for human life.1

Sleep duration, sleep quality and alignment of sleep-wake time with the natural circadian rhythm (or biological clock of the body that synchronizes with natural light-dark cycle of a day) are all important aspects affecting both our physical and mental health.1

Some of these health effects are summarized below.

Chronic Diseases and Conditions

More and more scientific studies have shown that our organs and body functions work according to the circadian rhythm.

Therefore, chronic sleep deprivation (6 hours or less per 24-hour period) and disruption of circadian rhythm was found to increase the risks of many chronic diseases and disorders.26,29

These include all-cause mortality, overweight and obesity, diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, cardiovascular/heart disease, cancers, GI disorders/diseases, liver disease, cognitive function and memory impairment, Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, and poor mental health.1,4,13,14,20,21,26

Immune Health

In terms of immune health, chronic sleep deprivation induces chronic low-grade systemic inflammation in the body and impairs immune defense against infections and cancer cells.2,3

The immune system also works in synchrony with the circadian rhythm where different immune cells and functions peak at different time of the sleep-wake cycle.2,3

Hormonal Balance

The circadian rhythm regulates the endocrine (hormonal) system including secretion of certain hormones including cortisol (aka stress hormone), melatonin (aka sleep hormone), leptin (aka satiety hormone), insulin, thyroid stimulating hormone, growth hormone, and prolactin.4,5

Disruption to the circadian rhythm due to poor lifestyle habits or other factors therefore contributes to hormonal imbalance which in turn cascades into many health issues.

Overall, maintaining a healthy sleep-wake cycle by sleeping before 10-11pm to be in-sync with the natural circadian rhythm, and having adequate amount of sleep of 7-8 hours (for adults) are important for our health.

Factors Contributing to Sleep Issues

Common sleep issues include difficulty falling asleep or insomnia, difficulty staying asleep, poor sleep quality, difficult getting up in the morning and waking up feeling unrested.19

There are overt health conditions that can disrupt sleep, such as chronic pain, obstructive sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome, liver disease, Parkinson’s disease, cancers, etc.18,21–23 These health conditions should be addressed accordingly.

In this article, we focus the discussion on more subtle health conditions that contribute to sleep issues.

There are two main hormones that drive the sleep-wake cycle in the body, i.e., cortisol (aka stress hormone) and melatonin (aka sleep hormone).

Factors that disrupt or deregulate the secretion of these hormones will affect our sleep.

Stress and Cortisol Dysregulation

Cortisol, the major stress hormone in the body, prepares the body for actions by mobilizing blood glucose for energy production, increasing blood circulation to skeletal muscles, etc.

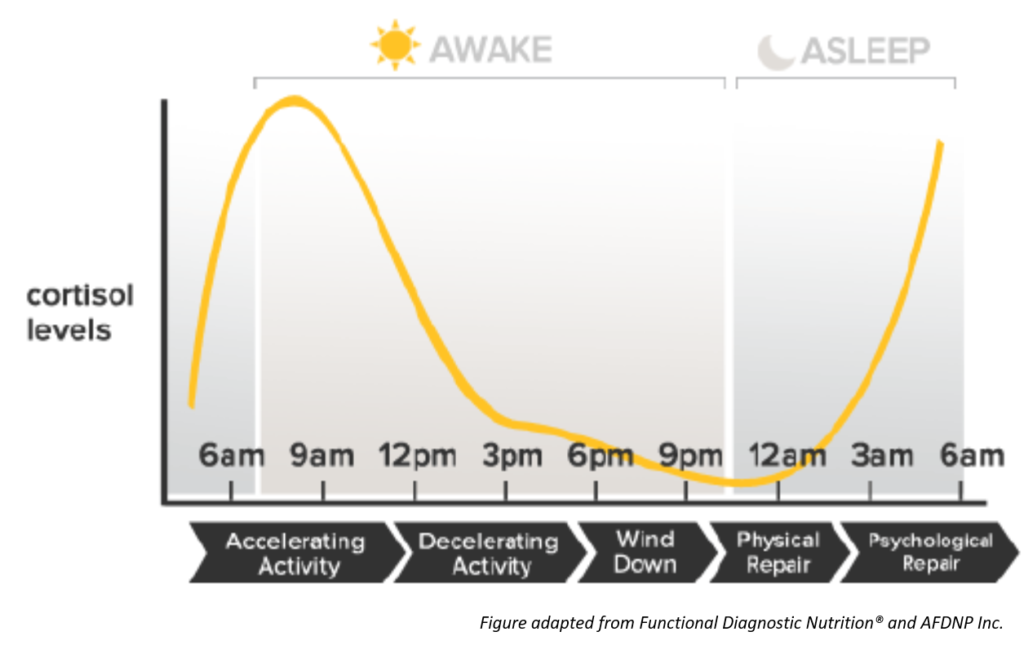

The release of cortisol by the adrenal glands follow a circadian pattern (see Figure 1 below). Cortisol levels are the highest upon waking in the morning preparing the body for the daily tasks. Cortisol levels continue to decline throughout the day and is the lowest at bedtime, preparing the body for rest.6

Figure 1. Circadian Pattern of Cortisol Levels

Chronic stress can disrupt the circadian pattern of cortisol levels. The disruption can manifest into elevated cortisol levels at night, thus resulting in difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep.6

The disruption can also manifest into depressed cortisol levels in the morning, resulting in difficulty waking up in the morning.6

Chronic stress can be mental or emotional in origin, but can also be due to chronic physical/physiological stressors including:7–10

- Exposure to environmental toxins (e.g., from foods, personal care and household products, and environment).

- Inappropriate diets causing digestive strain and blood sugar regulation problem.

- Food allergies and sensitivities that trigger immune reaction.

- Chronic inflammation.

- Chronic infections (e.g. parasites, bacteria, viruses, fungi).

- Sleep deprivation and disruption of circadian rhythm.

- Injuries.

- Physical strain.

For more details on how stress causes cortisol dysregulation and affects many aspects of our health, please check my previous article: Why Stress is the Culprit.

Gut Health and Melatonin

Melatonin, often known as the sleep hormone, regulates the circadian rhythm and sleep-wake cycles.4

The production of melatonin by the pineal gland in the brain is regulated by the normal light/dark conditions. The pineal gland secretes melatonin when it is dark at night to prepare the body to go to sleep, while the secretion of melatonin is suppressed by day light.4

In addition to the pineal gland, cells on the gut lining or mucosal barrier also produces melatonin. The gut lining produces 400 times more melatonin than the pineal gland. As opposed to the pineal gland, the production of melatonin by the gut is not governed by the circadian rhythm.11,12

Melatonin is not just a sleep hormone, it is also an important regulator of many biological functions including GI functions (e.g., food intake, digestion, GI motility, inter-organ communication between liver and gut, intestinal permeability), reproductive function, immune function, and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory defenses.11,12

Therefore, dysfunction of the gut or GI tract may compromise melatonin production, thus affecting sleep and other metabolic functions regulated by melatonin.

Gut dysfunction may include leaky gut (or intestinal permeability), gut inflammation, dysbiosis and pathogenic infections, etc.

For more details about how gut dysfunction affects many aspects of our health and what causes gut dysfunction, please check my previous article: Why Your Gut Feeling Matters.

Gut Microbiota and Sleep

Gut microbiota is an ecological community of commensal, symbiotic and pathogenic microorganisms found in the GI tract. These microorganisms include bacteria, fungi, viruses, archaea, and protists.

A healthy composition of gut microbiota is important for the health of the human host, including digestive and GI health, immune health, brain health, etc. For more details on the importance of gut microbiota to human health, please check out my previous article: Why Your Gut Feeling Matters.

Studies has shown that sleep deprivation can alter gut microbiota composition. On the other hand, higher diversity in gut microbiota composition is associated with increased sleep efficiency and total sleep time.14

Chronic Parasitic Infections

Parasitic infections may be much more common than what people might think, even in developed countries.

For example, in the U.S., it is estimated that over 11% of the population are infected with a parasite called Toxoplasma gondii. One can get infected by coming into contact with cat feces containing the parasite, contaminated raw meats, and contaminated raw fruits and vegetables.

People infected with T. gondii often do not exhibit clinically identifiable symptoms or exhibit non-specific wide range of clinical presentations. In addition, the parasite can remain inactive in the body for a long time and become reactivity if the person becomes immunosuppressed. As a result, the infection is often go undetected for a long time.15

Parasites can disrupt the circadian rhythm of the host. In addition, parasites also exhibit their own biological rhythm wherein some parasites tend to be more active at night, causing disruption to sleep.16,17

Poor Sleep and Lifestyle Habits

Sleep dysregulation due to poor sleep habits can disrupt the natural circadian rhythm. Disruption of circadian rhythm in turns contributes to dysregulation of sleep related hormones including cortisol and melatonin.

Certain lifestyle habits can also disrupt the circadian rhythm by provoking stress-induced response (including cortisol secretion and invocation of sympathetic nervous system activity), such as performing moderate-to-high intensity physical exercise, or high mental intensity tasks in the evening.

Here is a list of poor sleep and lifestyle habits that can affect sleep:

- Chronic or habitual shift in sleep-wake cycle that disrupt the natural circadian rhythm, including shift work, chronic or frequent jetlag, habitual sleeping past midnight, and irregular sleep and wake-up time (social jetlag).26,29

- Exposure to blue light (emitted from computer and device screens and from artificial lighting) in the evening which suppresses melatonin, promotes alertness, and shifts the circadian clock to a later time. Among the different types of artificial lights, LED light is the worst, followed by fluorescent light and then incandescent light. LED light has much higher and peak emission intensity at the blue light region (at wavelength of 450–470 nm).24,25

- Eating close to bedtime (i.e., the inactive phase of the circadian rhythm), which can increase sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity and disrupt the circadian rhythm.30,31

- Consuming caffeinated drinks or foods late in the afternoon or evening.28

- Consuming alcohol before bedtime which can increase arousal during second half of the night.28

- Consuming tobacco or nicotine containing products, which can contribute to sleep disturbance.28

- Engaging in moderate-to-high intensity physical exercise in the evening.

- Engaging in high mental intensity tasks or mentally/emotionally stressful activity in the evening.

- Exposure to electromagnetic radiation (e.g. from wireless devices, Wi-Fi etc.) prior to or during sleep, which can alter brain waves and induce cortical excitability resulting in disrupted and nonrestorative sleep.27

Tips for Better Sleep

For improved sleep, the factors contributing to sleep issues described in the previous section should be addressed.

Here is a list of practice for sleep hygiene (good sleep habits):

- Align sleep timing with the natural circadian rhythm (that synchronizes with the 24-hour light-dark conditions), by sleeping before 10-11pm at night and for a duration of 7-8 hours to avoid sleep deprivation.

- Maintain a regular sleep schedule to allow entrainment to the natural circadian rhythm.

- Minimize or reduce exposure to artificial light, especially blue light, from wireless devices and artificial lighting, by dimming light in the house and minimizing screen time (e.g. from wireless devices, etc.) in the evening.

- Establish a bedroom environment that is conducive to sleep, including sleep in a pitch-dark and quiet room, with comfortable bedding, etc.

- Reduce exposure to electromagnetic radiation by placing wireless devices outside of the bedroom or switching the devices to airplane mode and turning off Wi-Fi router at night.

- Eat the last meal of the day at least 3 hours before bedtime to allow active digestion to be completed before bedtime.

- Avoid caffeinated drinks or foods in late afternoon and evening.

- Avoid alcohol before bedtime.

- Avoid tobacco or nicotine containing products.

- Unwind and prepare the body to be in resting and parasympathetic mode 2-3 hours before bedtime, by avoiding moderate-to-high intensity physical activities and mentally/emotionally stressful activities, and engaging in relaxation activities (e.g., taking warm bath, listening to relaxation music, gentle yoga or stretching, meditation, etc.).

- Perform regular physical exercise during the day to help regulate circadian rhythm. Moderate-to-high intensity exercise during early part of the day support alignment with the circadian pattern of cortisol levels.32–34

- In case jetlag could not be avoided, support the body in entraining to the local 24-hour light-dark conditions by aligning sleep and daytime activities with the local time, exposure to sunlight and performing moderate-to-high intensity exercise in the morning.

In addition to sleep hygiene, some deeply rooted issues affecting sleep as described in the previous section should also be addressed. These include:

- Manage mental and emotional stress by addressing the sources of stress and employ relaxation techniques such as yoga, Tai Chi, meditation, low-intensity exercise, music therapy, etc.

- Address physical/physiological stressors which often can be overlooked, including toxin exposure from foods and environment, inappropriate diets causing digestive strain and blood sugar fluctuation, food sensitivities, chronic infections, chronic inflammation, over-exertion, etc.

- Address gut dysfunction and improve gut health and gut microbiota.

- Address chronic parasite infections which often can be hidden and causing a wide range of non-specific symptoms.

Related Articles

References

-

- Grandner MA. Sleep, Health, and Society. Sleep Med Clin. 2017;12(1):1‐22. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2016.10.012

- Almeida C, Malheiro A. Sleep, immunity and shift workers: A review. Sleep Science, 2016;9(3):164-168. doi:10.1016/j.slsci.2016.10.007

- Besedovsky L, Lange T, Born J. Sleep and immune function. Pflügers Archiv – European Journal Of Physiology, 2011;463(1):121-137. doi:10.1007/s00424-011-1044-0

- Serin Y, Acar Tek N. Effect of Circadian Rhythm on Metabolic Processes and the Regulation of Energy Balance. Ann Nutr Metab. 2019;74(4):322‐330. doi:10.1159/000500071

- Li J, Vitiello MV, Gooneratne NS. Sleep in Normal Aging. Sleep Med Clin. 2018;13(1):1‐11. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2017.09.001

- Adam EK, Quinn ME, Tavernier R, McQuillan MT, Dahlke KA, Gilbert KE. Diurnal cortisol slopes and mental and physical health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;83:25‐41. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.05.018

- Agorastos A, Nicolaides NC, Bozikas VP, Chrousos GP, Pervanidou P. Multilevel Interactions of Stress and Circadian System: Implications for Traumatic Stress. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:1003. Published 2020 Jan 28. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.01003

- Belda X, Fuentes S, Daviu N, Nadal R, Armario A. Stress-induced sensitization: the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and beyond. Stress. 2015;18(3):269‐279. doi:10.3109/10253890.2015.1067678

- Godoy LD, Rossignoli MT, Delfino-Pereira P, Garcia-Cairasco N, de Lima Umeoka EH. A Comprehensive Overview on Stress Neurobiology: Basic Concepts and Clinical Implications. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:127. Published 2018 Jul 3. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00127

- Dayas CV, Buller KM, Crane JW, Xu Y, Day TA. Stressor categorization: acute physical and psychological stressors elicit distinctive recruitment patterns in the amygdala and in medullary noradrenergic cell groups. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14(7):1143‐1152. doi:10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01733.x

- Chen CQ, Fichna J, Bashashati M, Li YY, Storr M. Distribution, function and physiological role of melatonin in the lower gut. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(34):3888-98.

- Claustrat B, Leston J. Melatonin: Physiological effects in humans. Neurochirurgie. 2015;61(2-3):77-84. doi:10.1016/j.neuchi.2015.03.002

- Forsyth CB, Voigt RM, Burgess HJ, Swanson GR, Keshavarzian A. Circadian rhythms, alcohol and gut interactions. Alcohol. 2015;49(4):389‐ doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2014.07.021

- Smith RP, Easson C, Lyle SM, et al. Gut microbiome diversity is associated with sleep physiology in humans. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0222394. Published 2019 Oct 7. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222394

- Ben-Harari RR, Connolly MP. High burden and low awareness of toxoplasmosis in the United States. Postgrad Med. 2019;131(2):103‐108. doi:10.1080/00325481.2019.1568792

- Downton P, Early JO, Gibbs JE. Circadian rhythms in adaptive immunity [published online ahead of print, 2019 Dec 14]. Immunology. 2019;10.1111/imm.13167. doi:10.1111/imm.13167

- Reece SE, Prior KF, Mideo N. The Life and Times of Parasites: Rhythms in Strategies for Within-host Survival and Between-host Transmission. J Biol Rhythms. 2017;32(6):516‐533. doi:10.1177/0748730417718904

- Ramar K, Olson EJ. Management of common sleep disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(4):231‐238.

- Chokroverty S. Overview of sleep & sleep disorders. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:126‐140.

- Wijarnpreecha K, Thongprayoon C, Panjawatanan P, Ungprasert P. Short sleep duration and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(11):1802‐1807. doi:10.1111/jgh.13391

- Marin-Alejandre BA, Abete I, Cantero I, et al. Association between Sleep Disturbances and Liver Status in Obese Subjects with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Comparison with Healthy Controls. Nutrients. 2019;11(2):322. Published 2019 Feb 2. doi:10.3390/nu11020322

- Albers JA, Chand P, Anch AM. Multifactorial sleep disturbance in Parkinson’s disease [published correction appears in Sleep Med. 2017 Sep;37:226]. Sleep Med. 2017;35:41‐48. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2017.03.026

- Medysky ME, Temesi J, Culos-Reed SN, Millet GY. Exercise, sleep and cancer-related fatigue: Are they related?. Neurophysiol Clin. 2017;47(2):111‐122. doi:10.1016/j.neucli.2017.03.001

- Chang AM, Aeschbach D, Duffy JF, Czeisler CA. Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(4):1232‐1237. doi:10.1073/pnas.1418490112

- Tosini G, Ferguson I, Tsubota K. Effects of blue light on the circadian system and eye physiology. Mol Vis. 2016;22:61‐72. Published 2016 Jan 24.

- Touitou Y, Reinberg A, Touitou D. Association between light at night, melatonin secretion, sleep deprivation, and the internal clock: Health impacts and mechanisms of circadian disruption. Life Sci. 2017;173:94‐106. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2017.02.008

- Zhang J, Sumich A, Wang GY. Acute effects of radiofrequency electromagnetic field emitted by mobile phone on brain function. Bioelectromagnetics. 2017;38(5):329‐338. doi:10.1002/bem.22052

- Irish LA, Kline CE, Gunn HE, Buysse DJ, Hall MH. The role of sleep hygiene in promoting public health: A review of empirical evidence. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;22:23‐36. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2014.10.001

- Potter GD, Skene DJ, Arendt J, Cade JE, Grant PJ, Hardie LJ. Circadian Rhythm and Sleep Disruption: Causes, Metabolic Consequences, and Countermeasures. Endocr Rev. 2016;37(6):584‐608. doi:10.1210/er.2016-1083

- Pickel L, Sung HK. Feeding Rhythms and the Circadian Regulation of Metabolism. Front Nutr. 2020;7:39. Published 2020 Apr 17. doi:10.3389/fnut.2020.00039

- Bo S, Broglio F, Settanni F, et al. Effects of meal timing on changes in circulating epinephrine, norepinephrine, and acylated ghrelin concentrations: a pilot study. Nutr Diabetes. 2017;7(12):303. Published 2017 Dec 18. doi:10.1038/s41387-017-0010-0

- Wolff CA, Esser KA. Exercise Timing and Circadian Rhythms. Curr Opin Physiol. 2019;10:64‐69. doi:10.1016/j.cophys.2019.04.020

- Lewis P, Korf HW, Kuffer L, Groß JV, Erren TC. Exercise time cues (zeitgebers) for human circadian systems can foster health and improve performance: a systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018;4(1):e000443. Published 2018 Dec 5. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000443

- Hill EE, Zack E, Battaglini C, Viru M, Viru A, Hackney AC. Exercise and circulating cortisol levels: the intensity threshold effect. J Endocrinol Invest. 2008;31(7):587‐591. doi:10.1007/BF03345606