Although stress is often thought of as psychological or mental in origin, stress can present itself in multiple forms such as physical injuries/trauma, over-exercise, sleep deprivation, inappropriate diets, infections, chronic inflammation and environmental toxins.

Stressor is any real or imagined situation, circumstance, or stimulus that is perceived to be a threat to the body, resulting in a series of physiological response and adaptation1.

When stress becomes chronic, physiological maladaptation occurs including dysregulation of cortisol (the primary stress hormone in the body), resulting in widespread dysfunction of various organs and body functions, which eventually manifests into certain signs, symptoms and health challenges.

Therefore, systematically identifying and resolving stressors to our body is an important step toward rebuilding our health. Learn more about how Function Health Coaching may help to rebuild your health.

The Multifaceted Form of Stress that Challenges Our Health

Figure 1. Different Types of Stressors

Stressors can be externally imposed or hidden internally in our body (see Figure 1).

External stressors can be categorized into:

- Mental and emotional stressors: include fear, guilt, worry, anxiety, grief, trauma and abuse, job-related stress and relationship stress.

- Existential angst: includes lack of purpose or meaning in life, hopelessness and despair.

- Physical/biomechanical stressors: include musculoskeletal misalignment, fractures, muscle injuries, nerve compression, poor posture, and over-exercise.

Internal stressors are biochemical and physiological stressors occurring inside the body, including:

- Eating the wrong diet causing digestive strain and blood sugar regulation problem.

- Food sensitivities/intolerances, allergies and over-active immune system.

- Pathogenic infections (e.g., parasites, bacteria, viruses, fungi).

- Chronic inflammation.

- Sleep deprivation.

- Exposure to environmental toxins (e.g., pesticides, herbicides, heavy metals, food additives and chemicals, toxic chemicals in personal care products and household consumables, endocrine disruptors).

- Electro-magnetic radiation.

In our modern lifestyle, we are often bombarded with many of these external and internal stressors on a daily basis, resulting in chronic stress and detrimental health effects.

Good Stress vs. Bad Stress

Although stressors result in a series of physiological response and adaptation in the body, not all stressors are bad.

As depicted by the Yerkes-Dodson principle1,

- Eustress or good stress is any stressor that promotes growth and development in the body towards improved level of health and wellbeing. For example, adequate level of physical exercise can be eustress that promotes musculoskeletal and cardiovascular health.

- Distress or bad stress occurs when a stressor persists beyond the optimal level (e.g., over-exercise) resulting in detrimental physiological effects.

Distress can be acute or chronic.

- Acute stress is usually caused by rapid-onset stressors that are intense but last for a short duration. The body typically returns to homeostasis, a physiological state of calmness and balance, when stressors dissipate.

- Chronic stress occurs when stressors persist for a long duration, wherein the body continues to perform physiological adaptation in an attempt to return to homeostasis. As depicted by Hans Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) 1, the body enters the stage of resistance, and eventually the stage of exhaustion, wherein the body can no longer meet the demands placed upon it, resulting in dysfunction of one or more organs and body functions.

In our modern life, as we are bombarded with many types of stressors on a daily basis, chronic stress and maladaptation are common phenomena.

How Our Body Responses to Stress?

The hypothalamus, an organ in the brain, is the command center for stress response.

When simulated by stressors, the hypothalamus activates the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the medulla of adrenal glands to secrete the neurotransmitters/hormones called catecholamines, comprising of epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline), to prepare the body for immediate fight-or-flight response.

If stressors persist beyond several minutes, the hypothalamus, in conjunction with the pituitary gland in the brain activate the adrenal cortex to produce cortisol, the major stress hormone in the body, as well as other corticosteroid hormones including aldosterone. Cortisol has prolonged effects in the body that can last for hours, days or weeks.

Both the SNS (producing catecholamines) and cortisol are key mediators of stress response in the body. When a stressor is encountered, these mediators trigger physiological adaptation and rapid metabolic change to prepare the body for fight-or-flight response and increased energy expenditure.

Such body adaptation includes1:

- Increased blood pressure and heart rate to bring oxygen and nutrients to skeletal muscles

- Increased serum glucose and free fatty acids for energy metabolism

- Increased neural activity to muscles

- Deprioritization of certain body functions such as digestion and elimination, cell and tissue repair

- Breaking down of tissues and glycogen/fat/protein storage in order to mobilize glucose, free fatty acids and amino acids for energy metabolism.

The Widespread Health Effects of Stress-Induced Cortisol Dysregulation

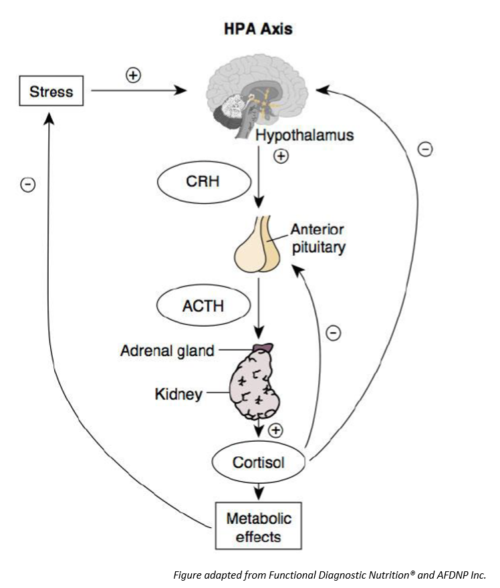

Figure 2. The HPA Axis

The physiological pathway of the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland and the adrenal cortex is called the HPA axis (see Figure 2).

The dysfunction of the HPA axis that results in dysregulation of the release and circulating levels of cortisol in the body is the cause of many stress-related disorders.

The term adrenal fatigue is often used to describe the functional disorder characterized by inability of the adrenal cortex to produce adequate levels of cortisol to respond to stress and daily operation of the body. However, adrenal fatigue is just one manifestation of a late-stage HPA axis dysfunction.

There are different manifestations and stages of HPA axis dysfunction that progress from disrupted circadian release of cortisol and chronically elevated cortisol level to subsequent chronically depressed cortisol levels.

Chronically Elevated Cortisol Levels

This is an early stage of the progression of HPA axis dysfunction, which has been associated with multitude of systemic effects including2–5:

- Suppression of immune function such as natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity and immunoglobulin A (IgA) secretion

- Increased risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs)

- Gastrointestinal (GI) disturbance due to increased gastric acid secretion and disruption of intestinal microflora

- insulin resistance and hyperglycemia

- Reduced diuresis

- Reduced bone formation

- Impaired thyroid hormone production

- Increased abdominal fat

- Hippocampal damage that increases the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease

Chronically Depressed Cortisol Levels

This is a characteristic of late-stage HPA axis dysfunction and often called adrenal fatigue, which results in a loss of counter-regulation to immune system and proinflammatory cytokine activation, and SNS activity. These in turn contribute to2–3:

- Autoimmune disorders and allergies

- Chronic pain

- Fibromyalgia

- Chronic fatigue syndrome

- Posttraumatic stress disorder

- Glucose dysregulation and hypoglycemia

- Obesity

Disruption of the Circadian Release of Cortisol

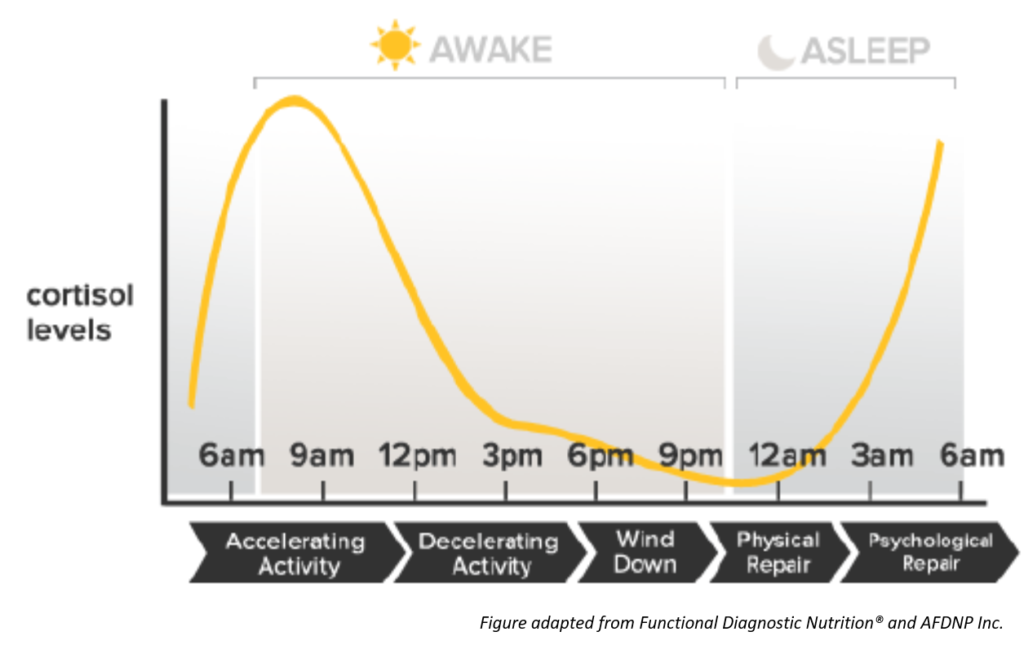

Figure 3. Circadian Pattern of Cortisol

The release of cortisol by the adrenal glands follow a circadian pattern (see Figure 3). Cortisol levels are the highest upon awake in the morning preparing the body for the daily tasks. Cortisol levels continue to decline throughout the day and is the lowest at bed time, preparing the body for rest.

Disruption in the circadian pattern of cortisol can occur at various stages of HPA axis dysfunction. It can also be caused by poor sleep routine and habits. Disruption of circadian cortisol pattern has been associated with tumor growth, metabolic syndrome, and increased coronary artery calcification3.

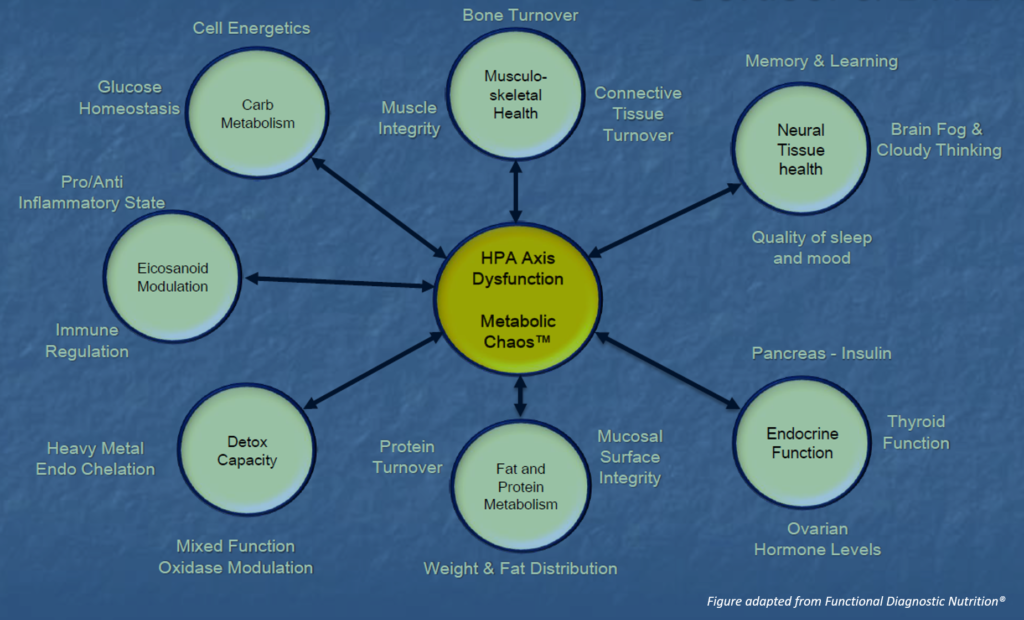

How HPA Axis Dysfunction Cascades to Various Body Systems

The effects of HPA axis dysfunction on various foundational body systems are illustrated in Figure 3 below.

Figure 4. Cascading Effects of HPA Axis Dysfunction

As illustrated by the “double-arrows”, HPA axis dysfunction can be the cause of dysfunction of certain body systems. On the other hand, dysfunction of certain body systems can be the hidden stressors that contribute to chronic stress and HPA axis dysfunction.

From Figure 4, we can also see how imbalance and dysfunction in one body system can trigger cascading effects onto other body systems.

Signs or symptoms may not be apparent during early stages of underlying dysfunction. When overt signs or symptoms appear, the underlying dysfunction has typically progressed to an advanced stage.

Our human body is complex and sophisticated, signs and symptoms that appear on the surface often do not point directly at the underlying dysfunctions. For example, sex hormone imbalance such as estrogen dominance or estrogen deficiency, and thyroid hormone imbalance are often the result and manifestation of some deeper level dysfunction and hidden stressors in the body.

Holistic Health Approach to Stress Management

A holistic health rebuilding approach focuses on identifying and addressing both the overt and hidden stressors and underlying dysfunctions in the body, and providing the body as a whole with what it needs to heal and restore homeostasis, rather than mere suppression of specific signs and symptoms.

Learn more about how Functional Health Coaching may help to rebuild your health.

Related Articles

References

- Seaward B. Managing Stress: Principles And Strategies For Health And Well-Being. 8th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2014.

- Cook S. Current Controversy: Does Adrenal Fatigue Exist?. Natural Medicine Journal. https://www.naturalmedicinejournal.com/journal/2017-10/current-controversy-does-adrenal-fatigue-exist. Published 2017.

- Edwards L, Heyman A, Swidan S. Hypocortisolism: An evidence-based review. Integrative Medicine A Clinician’s Journal. 2011;10(4):30-37.

- Ennis G, An Y, Resnick S, Ferrucci L, O’Brien R, Moffat S. Long-term cortisol measures predict Alzheimer disease risk. Neurology. 2016;88(4):371-378. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000003537

- Head K, Kelly G. Nutrients and botanicals for treatment of stress: Adrenal fatigue, neurotransmitter imbalance, anxiety, and restless sleep. Alternative Medicine Review. 2009;14(2):114-140.