Join our mailing list to receive the latest health tips and updates.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Why Adopt an Anti-inflammatory Diet & Lifestyle and How?

Chronic inflammation and the associated oxidative stress have been found by numerous scientific studies to be the major culprits of many chronic diseases/disorders that have become so prevalent in our modern society.

These chronic diseases/disorders include obesity, type-2 diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease/dementia, mental disorders, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, osteoporosis, etc.1–8

There is also a strong association between chronic inflammation and aging and age-related chronic diseases, wherein the term ‘inflamm-aging’ has been coined.9–10

Many factors can contribute to chronic inflammation including diet and lifestyle factors, as well as exposure to environmental toxins.

Therefore, it makes sense to try to avoid or mitigate these risk factors so that we can reduce the risks of chronic diseases/disorders.

In this article, I share evidence-based information on how chronic inflammation affects our health and tips to adopt an anti-inflammatory diet and lifestyle.

For a quick summary of the tips to adopt an anti-inflammatory diet and lifestyle, you can go directly to the Summary section.

Topic List

What is Chronic Inflammation and How it Affects Health?

Chronic Inflammation and Oxidative Stress – A Vicious Cycle

Factors That Promote Chronic Inflammation (and Oxidative Stress)

Body’s Internal Biological/Physiological Conditions

Tips for Anti-inflammatory Diet and Lifestyle

Strategies to Improve Body’s Internal Biological/Physiological Conditions

Summary

Unlike acute phase (short-lived) inflammation which is an essential part of a healthy immune function, chronic inflammation causes collateral damage in cells and tissues, and has many adverse health effects, as described in section What is Chronic Inflammation and How it Affects Health?

Chronic inflammation is tightly coupled with oxidative stress, wherein both are joint culprits to many chronic diseases/disorders, as described in section Chronic Inflammation and Oxidative Stress – A Vicious Cycle.

There are many factors that can promote chronic inflammation in the body, including diet, lifestyle, environment, and body’s internal biological/physiological conditions and environment. This is described in section Factors That Promote Chronic Inflammation (and Oxidative Stress).

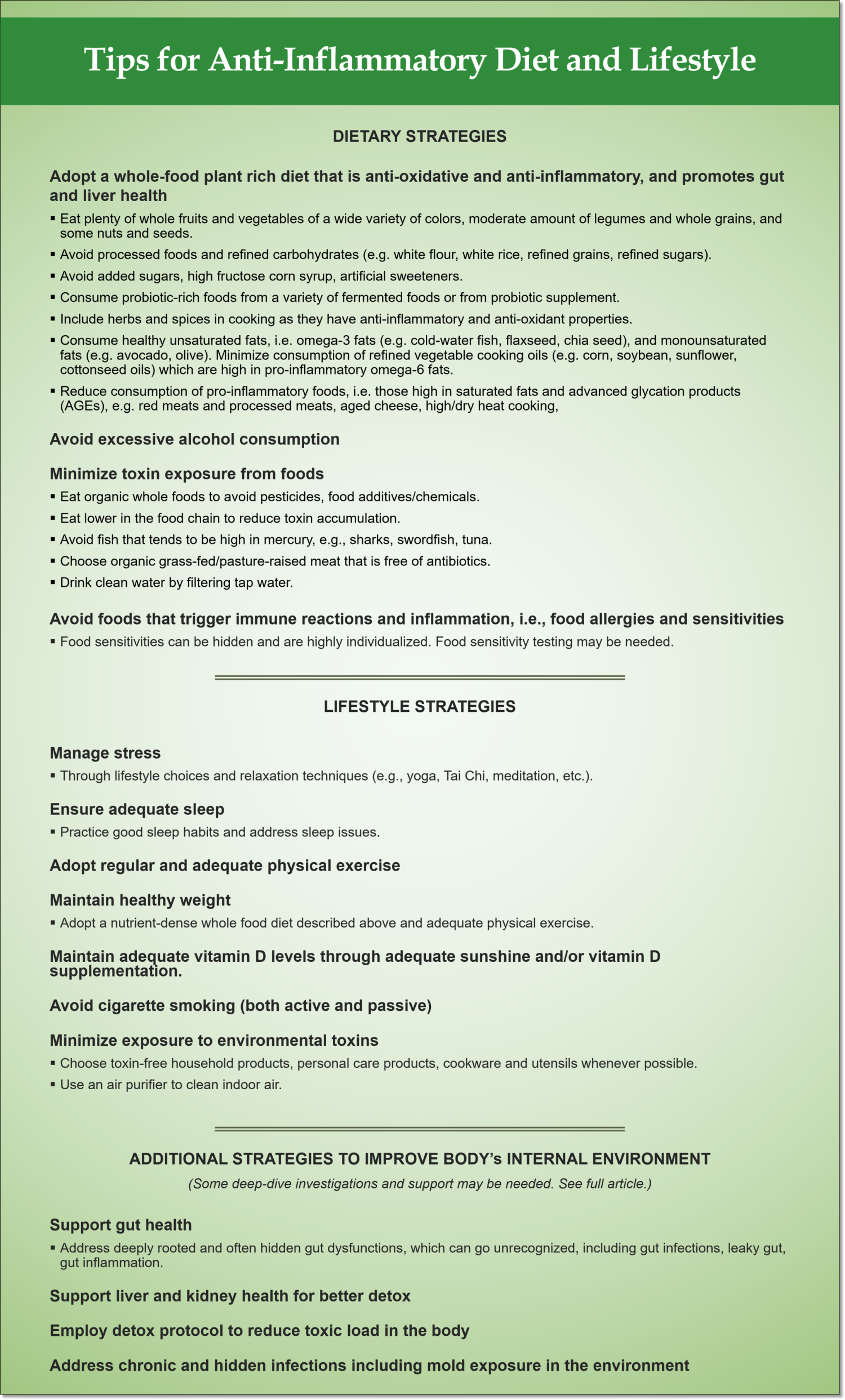

A quick summary of tips to mitigate the risk factors of chronic inflammation is given below (for full details, see section Tips for Anti-inflammatory Diet and Lifestyle).

For additional support in addressing deeply rooted issues including gut, liver and detox issues and food allergies/sensitivities, please check out Functional Health Coaching.

What is Chronic Inflammation and How it Affects Health?

Normal Inflammatory Process

It is important to note that inflammation by itself is an essential part of a normal immune function. It is part of the body’s first-tier immune defense called the innate (or non-specific) immune system.11,12,15

During infection or tissue injury caused by internal or foreign agents (e.g., pathogens, chemical/toxin exposure, physical injury, etc.), normal and acute phase inflammatory response is triggered to mobilize immune mediators and immune cells, confine and prevent further tissue damage, and clean out debris to set the stage for repair and recovery.11,12,15

The classical symptoms of inflammation that we may have experienced when physical injury occurs, including swelling, redness, pain, and warmth, are part of the healing process.11,12

Normal inflammatory process should be short-lived and subside after the internal/external triggering factors have been resolved.12,15

Chronic Inflammation

Inflammation becomes an issue when it persists and does not arrive to a resolution state. A chronic low-grade systemic inflammation can result. Chronic inflammation can be due to unresolved chronic infections, on-going exposure to chemicals/toxins and other inflammation-triggering agents and biological factors.12,15 Diet, lifestyle, environmental and biological factors that promote chronic inflammation are discussed in the next section.

Chronic inflammation causes on-going cell and tissue damage and dysfunction in the body, leading to dysfunction, disorders and diseases.12,15

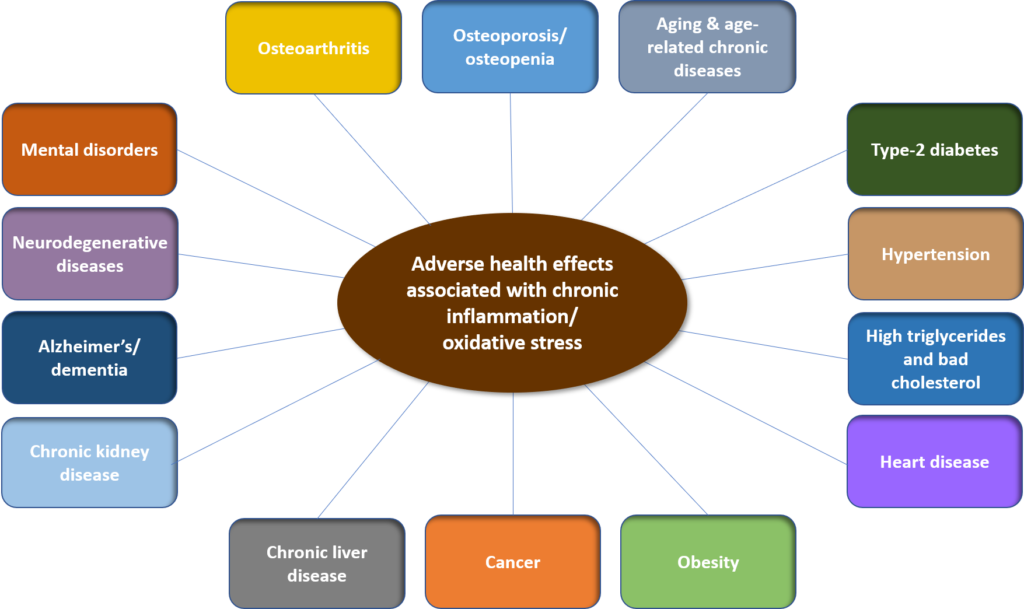

Figure 1. Chronic diseases/disorders associated with chronic inflammation

As shown in Figure 1 above, numerous scientific studies have shown that chronic inflammation is a major underlying disease process and culprit of many chronic diseases/disorders, including1–10,12–18

- Blood sugar elevation, insulin resistance and type-2 diabetes

- Hypertension

- High triglycerides and bad cholesterol

- Heart disease

- Obesity

- Cancer

- Chronic liver disease

- Chronic kidney disease

- Alzheimer’s disease and dementia

- Mental disorders (incl. depression, PSTD, depression, etc.)

- Neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis, etc.)

- Osteoarthritis

- Bone loss, osteopenia and osteoporosis

- Aging and aged-related disorders/diseases including some of those listed above

In addition to the above-listed chronic diseases/disorders, out-of-control inflammatory response and cytokine (immune mediators) storm were found to play important roles in disease severity and mortality from COVID-19, progressing from pneumonia (inflammation of the lung) to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and multi-organ dysfunction, eventually leading to mortality.19–22

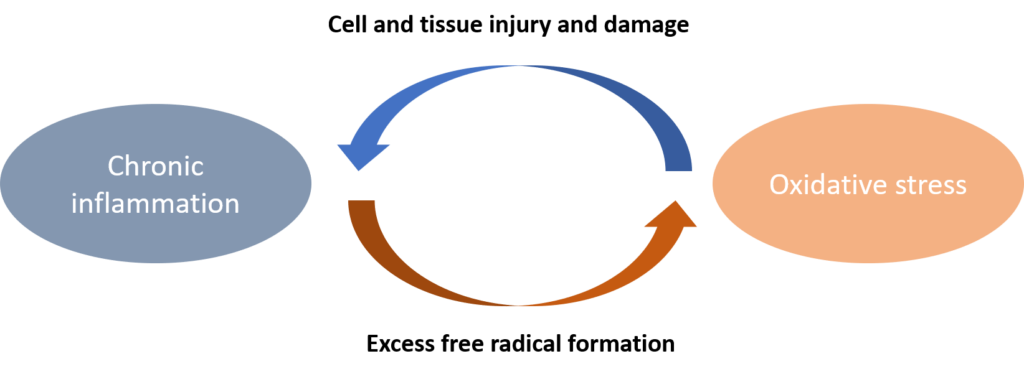

Chronic Inflammation and Oxidative Stress – A Vicious Cycle

Figure 2. Tight coupling between chronic inflammation and oxidative stress

Free radicals or oxidants are produced by normal metabolic processes in the body. Inflammatory process also produces free radicals.

Free radicals can attack (or oxidize) cells and tissues causing damage.

The body has natural antioxidants to neutralize excess free radicals. In a normal and healthy body condition, there is a balance between free radical formation and the antioxidant defense mechanism.12

In the case of chronic systemic inflammation, the persistent generation of free radicals can overwhelm the antioxidant capacity of the body, resulting in oxidative stress.12

Oxidative stress causes cell and tissue injury and damage, which in turn trigger inflammatory response.12

Therefore, chronic inflammation and oxidative stress often potentiate one another, resulting in a vicious cycle, as shown in Figure 2 above.23–26

Both chronic inflammation and oxidative stress are the joint culprits to many chronic diseases/disorders as previously discussed.23–26

Factors That Promote Chronic Inflammation (and Oxidative Stress)

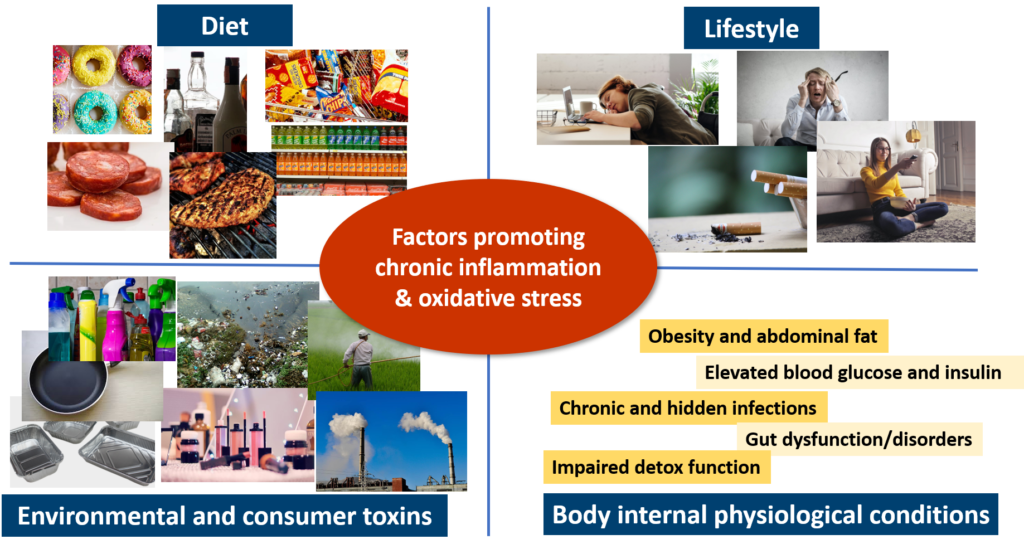

There are many factors that can promote chronic inflammation in the body, including diet, lifestyle, environment, and body’s internal biological/physiological conditions.

Figure 3. Factors that promote chronic inflammation and oxidative stress

Diet

Diet that promotes chronic inflammation include:23,27–35,62,63

- Saturated fats (e.g., meat especially red meat and processed meat).

- High ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 polyunsaturated fats (e.g., some refined vegetable oils such as corn, soybean, sunflower and cottonseed oils), because omega-6 fats is pro-inflammatory.

- Advanced glycation end products (AGEs), found in cooked or uncooked meat especially beef, poultry and pork, fish, and aged cheese. High and dry heat cooking increase the levels of AGEs in foods.

- High glycemic index or glycemic load carbohydrates, especially refined carbohydrates (e.g., white flour, white rice, other refined grains, refined sugars etc.).

- Industrial sweeteners namely high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) and refined sugar or table sugar (sucrose) found in processed foods, soft drinks and other sugar-sweetened beverages.

- Processed foods, which contains industrial sweeteners as mentioned above, refined carbohydrates, and food additives/chemicals.

- Deficiency in zinc and magnesium due to over-consumption of processed/refined foods that are generally low in micronutrients, as opposed to whole foods.

- Chronic and excessive alcohol consumption.

- Foods that trigger immune reactions, i.e., food allergies and sensitivities. Food allergies and sensitivities can contribute to autoimmunity and inflammation. Allergies/sensitivities to certain foods are highly individualized and related to gut dysfunction, in particular leaky gut (also called intestinal permeability).

- For more details, see my previous article: Tips to Promote Gut Health for a Healthy Body & Mind, Why Your Gut Feeling Matters.

Lifestyle

Lifestyle factors that promote chronic inflammation include:36–40,67

- Chronic stress (see more details in my previous article: Why Stress is the Culprit).

- Sleep deprivation and disrupted sleep-wake cycle.

- Cigarette smoking.

- Sedentary lifestyle and lack of physical exercise.

- Vitamin deficiency due to lack of sunshine and without adequate vitamin D supplementation.

Environment

In our modern living, toxins are ubiquitously present in our daily life.

Over the last few decades, over 80,000 industrial chemicals have been produced. These industrial chemicals are widely used in many aspects of our daily life:41–43

- Food supply, including food additives/chemicals, agricultural chemicals (e.g., pesticides, herbicides), food packaging, etc.

- Personal care and hygiene products.

- Household and consumer products, including clothing, cleaning products, household appliances, furniture, electronics, building materials, etc.

- Healthcare products, including certain drugs, and mercury used in dental amalgam, etc.

- Many of these chemicals are also released into the environment, ended up in the air, water, soil, and food chain.

The safety of many of these chemicals have not been tested and verified.41,43

On the contrary, many industrial chemicals commonly found in our daily life have been shown to exert detrimental effects in our health.

For more details, please check out my previous article: How Toxins Affect Your Health and Tips to Reduce Toxic Load.

With regards to chronic inflammation, toxins can trigger inflammation through various mechanisms including directly triggering release of pro-inflammatory signaling, or indirectly promoting oxidative stress and cellular damage resulting in inflammation.41

Body’s Internal Biological/Physiological Conditions

In addition to the above external factors, certain internal biological/physiological environment and conditions of the body can also promote chronic systemic inflammation throughout the body.

These include:1,44–61

- Obesity and abdominal fat.

- Note that as discussed above, chronic inflammation also promotes obesity. Thus, chronic inflammation and obesity can form a vicious cycle.

- Dysfunction in blood sugar regulation and insulin resistance, resulting in elevated blood glucose and insulin levels.

- Note that as discussed above, chronic inflammation also promotes insulin resistance and type-2 diabetes. Thus, a vicious cycle can be formed.

- Chronic and hidden infections (e.g., bacteria, virus, parasites, mold) that produce biological toxins (or biotoxins) in the body.

- Gut dysfunction and disorders such as leaky gut (also called intestinal permeability) and imbalanced gut microbiota (also called dysbiosis, i.e., overgrowth of bad microorganisms and undergrowth of good microorganisms) promote chronic systemic inflammation not just in the gut but also throughout the body.

- See more details in my previous article: Tips to Promote Gut Health for a Healthy Body & Mind, Why Your Gut Feeling Matters.

- Impaired detox function in the body which results in toxin accumulation in the body. In addition to the gut as discussed above, liver and kidneys are major detox organs in the body. Poor liver and/or kidney health can result in toxin accumulation.

Tips for Anti-inflammatory Diet and Lifestyle

Strategies to reduce chronic inflammation are those that involve minimizing or reducing the diet, lifestyle, environmental, and biological/physiological factors that promote chronic inflammation, as discussed in the previous section.

These strategies are summarized below.

Dietary Strategies

- Consume a whole food plant-rich diet – consisting of plenty of whole fruits and vegetables of a wide variety of colors, moderate amount of legumes and whole grains, and some nuts and seeds. Such a diets is rich in a wide range of antioxidants, fibers and other health promoting micronutrients and phytonutrients, which help to combat oxidative stress, promote anti-inflammatory response, and regulate blood sugar. Leafy greens, cruciferous vegetables, and berries are particularly beneficial.

- Consume probiotic-rich foods from a variety of fermented foods and/or probiotic supplement.

- Include herbs and spices in your cooking. They not only enhance flavor but many herbs and spices (e.g., thyme, oregano, rosemary, turmeric, cinnamon, cloves, ginger, cardamom, etc.) have anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties.64,65

- Consume healthy unsaturated fats that are anti-inflammatory including monounsaturated fats (e.g., olive, avocado) and omega-3 polyunsaturated fats (e.g., cold-water fish, flaxseed, chia seed, some nuts).

- Minimize or reduce consumption of refined vegetable oils that are high in pro-inflammatory omega-6 fats, such as corn, soybean, sunflower and cottonseed oils. Choose avocado oil as cooking oil as it has healthy unsaturated fats as well as high smoke point.66

- Minimize or reduce consumption of foods high in saturated fats and AGEs such as meats (especially red meats and processed meats), foods cooked in high/dry heat, and dairy products especially aged cheese.

- Avoid or minimize consumption of processed foods, which are typically filled with food additives/chemicals, artificial sweeteners, added sugars, high fructose corn syrup, and refined carbohydrates.

- Choose organic foods whenever possible, to minimize exposure to pesticides, herbicides and other agricultural chemicals.

- Avoid fish that tend to be high in mercury, including swordfish, marlin, king mackerel, orange roughy, etc. Check out EWG’s seafood guide at: https://www.ewg.org/research/ewgs-good-seafood-guide.

- Choose organic, grass-fed/pasture-raised meat that is free of antibiotics and lower in toxic chemical accumulation.

- Avoid excessive alcohol consumption.

- Drink clean water by filtering your tap water. check out EWG’s water filter guide at: https://www.ewg.org/tapwater/water-filter-guide.php.

- Avoid foods that trigger immune reactions and inflammation, i.e., food allergies and sensitivities. Food allergies and sensitivities can be highly individualized. Food sensitivities (not allergies) can often go unrecognized – some deep-dive investigation such as functional lab testing may be necessary.

Lifestyle Strategies

- Adopt adequate stress management strategies by addressing the sources of stress (e.g., through lifestyle adjustment) and practice relaxation techniques (e.g., yoga, Tai Chi, meditation, low-intensity exercise, music therapy, etc.)

- Ensure adequate sleep by practicing good sleep habits and addressing sleep issues.

- See more details in my previous article: Tips for Better Sleep to Support Your Immune Health and Overall Health.

- Adopt regular and adequate physical exercise, which has anti-inflammatory effects as well as for healthy weight management.

- See more details in my previous article: Choosing the Right Types of Exercise for Your Immune Health.

- Maintain healthy weight through nutrient-dense whole food diets (as described above) and adequate physical exercise.

- Maintain adequate vitamin D levels (i.e., blood serum 24(OH)D levels) through adequate sunshine and/or vitamin D supplementation.68–70

- Note that there are currently no international standardized thresholds for 25(OH)D to define vitamin D deficiency. Guidelines from different scientific societies and countries recommend 50 to 75 nmol/L as adequate.

- Minimize exposure to environmental toxins by choosing toxin-free household products, personal care products, cookware and utensils whenever possible. Use an air purifier to clean your indoor air.

- See more details in my previous article: How Toxins Affect Your Health and Tips to Reduce Toxic Load.

- Avoid cigarette smoking (both active and passive).

Strategies to Improve Body’s Internal Biological/Physiological Conditions

- Support gut health

- In addition to the above diet and lifestyle strategies, it is important to also address deeply rooted and hidden gut dysfunctions which can often go unrecognized, including gut infections, leaky gut, and gut inflammation. Some deep-dive investigation such as functional lab testing may be necessary.

- For more details on tips to support gut health, see my previous article: Tips to Promote Gut Health for a Healthy Body & Mind.

- Support liver health for better detox function

- In addition to the above diet and lifestyle strategies, for additional tips to support liver health, see my previous article: Take Care of Your Liver for Healthy Immunity and Overall Wellness.

- Support kidney health for better detox function

- The above-described diet and lifestyle strategies, and strategies for gut and liver health also promote kidney health.

- Employ detox protocol to reduce toxic load in the body

- For more details, see my previous article: How Toxins Affect Your Health and Tips to Reduce Toxic Load.

- Address chronic and hidden infections including mold exposure in the environment. Some deep-dive investigation such as functional lab testing may be necessary.

For additional support in addressing deeply rooted gut, liver and detox issues and food allergies/sensitivities, please check out Functional Health Coaching.

Related Articles

Tips to Promote Gut Health for a Healthy Body & Mind

How to Support Your Immune Health – See What Scientific Research Showed

How Toxins Affect Your Health and Tips to Reduce Toxic Load

Tips for Better Sleep to Support Your Immune Health and Overall Health

Take Care of Your Liver for Healthy Immunity and Overall Wellness

Choosing the Right Types of Exercise for Your Immune Health

References

- Esser N, Legrand-Poels S, Piette J, Scheen A, Paquot N. Inflammation as a link between obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;105(2):141-150. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2014.04.006

- Golia E, Limongelli G, Natale F et al. Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Target. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2014;16(9). doi:10.1007/s11883-014-0435-z

- Newcombe E, Camats-Perna J, Silva M, Valmas N, Huat T, Medeiros R. Inflammation: the link between comorbidities, genetics, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15(1). doi:10.1186/s12974-018-1313-3

- Moss S, Blaser M. Mechanisms of Disease: inflammation and the origins of cancer. Nature Clinical Practice Oncology. 2005;2(2):90-97. doi:10.1038/ncponc0081

- Murata M. Inflammation and cancer. Environ Health Prev Med. 2018;23(1). doi:10.1186/s12199-018-0740-1

- Daiber A, Lelieveld J, Steven S, et al. The “exposome” concept – how environmental risk factors influence cardiovascular health. Acta Biochim Pol. 2019;66(3):269-283. doi:10.18388/abp.2019_2853

- Pappachan JM, Babu S, Krishnan B, Ravindran NC. Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Clinical Update. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2017;5(4):384-393. doi:10.14218/JCTH.2017.00013

- Al-Dayyat HM, Rayyan YM, Tayyem RF. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and associated dietary and lifestyle risk factors. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2018;12(4):569-575. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2018.03.016

- Bektas A, Schurman SH, Sen R, Ferrucci L. Aging, inflammation and the environment. Exp Gerontol. 2018;105:10-18. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2017.12.015

- Neves J, Sousa-Victor P. Regulation of inflammation as an anti-aging intervention. FEBS J. 2020;287(1):43-52. doi:10.1111/febs.15061

- Marieb E, Hoehn K. Human Anatomy & Physiology. 10th ed. San Francisco: Pearson Benjamin Cummings; 2016.

- Arulselvan P, Fard MT, Tan WS, et al. Role of Antioxidants and Natural Products in Inflammation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:5276130. doi:10.1155/2016/5276130

- Hori H, Kim Y. Inflammation and post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;73(4):143-153. doi:10.1111/pcn.12820

- Leonard BE. Inflammation and depression: a causal or coincidental link to the pathophysiology?. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2018;30(1):1-16. doi:10.1017/neu.2016.69

- Furman D, Campisi J, Verdin E, et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat Med. 2019;25(12):1822-1832. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0675-0

- Bennett JM, Reeves G, Billman GE, Sturmberg JP. Inflammation-Nature’s Way to Efficiently Respond to All Types of Challenges: Implications for Understanding and Managing “the Epidemic” of Chronic Diseases. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:316. Published 2018 Nov 27. doi:10.3389/fmed.2018.00316

- Redlich K, Smolen JS. Inflammatory bone loss: pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11(3):234-250. Published 2012 Mar 1. doi:10.1038/nrd3669

- Stephenson J, Nutma E, van der Valk P, Amor S. Inflammation in CNS neurodegenerative diseases. Immunology. 2018;154(2):204-219. doi:10.1111/imm.12922

- Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. Published online March 13, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994

- Singhal T. A Review of Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19). Indian J Pediatr(2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-020-03263-6

- Li G, Fan Y, Lai Y, et al. Coronavirus infections and immune responses. J Med Virol. 2020; 92: 424– 432. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25685

- Han Q, Lin Q, Jin S, You L. Coronavirus 2019-nCoV: A brief perspective from the front line [published online ahead of print, 2020 Feb 25]. J Infect. 2020;S0163-4453(20)30087-6. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.010

- Tan BL, Norhaizan ME, Liew WP. Nutrients and Oxidative Stress: Friend or Foe?. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:9719584. Published 2018 Jan 31. doi:10.1155/2018/9719584

- Hacışevki A, Baba B. An Overview of Melatonin as an Antioxidant Molecule: A Biochemical Approach. In: Melatonin – Molecular Biology, Clinical and Pharmaceutical Approaches; 2018:59-85. doi:10.5772/intechopen.79421

- Singh A, Kukreti R, Saso L, Kukreti S. Oxidative Stress: A Key Modulator in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules. 2019;24(8):1583. Published 2019 Apr 22. doi:10.3390/molecules24081583

- Daenen K, Andries A, Mekahli D, Van Schepdael A, Jouret F, Bammens B. Oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34(6):975‐991. doi:10.1007/s00467-018-4005-4

- Mari-Sanchis A, Gea A, Basterra-Gortari F, Martinez-Gonzalez M, Beunza J, Bes-Rastrollo M. Meat Consumption and Risk of Developing Type 2 Diabetes in the SUN Project: A Highly Educated Middle-Class Population. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0157990. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157990

- Feskens E, Sluik D, van Woudenbergh G. Meat Consumption, Diabetes, and Its Complications. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13(2):298-306. doi:10.1007/s11892-013-0365-0

- Wilders-Truschnig M, Mangge H, Lieners C, Gruber H, Mayer C, März W. IgG antibodies against food antigens are correlated with inflammation and intima media thickness in obese juveniles. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2008;116(4):241–245. doi:10.1055/s-2007-993165

- Karakula-Juchnowicz H, Gałęcka M, Rog J, et al. The Food-Specific Serum IgG Reactivity in Major Depressive Disorder Patients, Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients and Healthy Controls. Nutrients. 2018;10(5):548. Published 2018 Apr 28. doi:10.3390/nu10050548

- Sharma N, Bhatia S, Chunduri V, et al. Pathogenesis of Celiac Disease and Other Gluten Related Disorders in Wheat and Strategies for Mitigating Them. Front Nutr. 2020;7:6. Published 2020 Feb 7. doi:10.3389/fnut.2020.00006

- Alwahsh SM, Gebhardt R. Dietary fructose as a risk factor for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Arch Toxicol. 2017;91(4):1545-1563. doi:10.1007/s00204-016-1892-7

- Lustig RH. Fructose: it’s “alcohol without the buzz”. Adv Nutr. 2013;4(2):226-235. Published 2013 Mar 1. doi:10.3945/an.112.002998

- Stanhope KL. Sugar consumption, metabolic disease and obesity: The state of the controversy. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2016;53(1):52-67. doi:10.3109/10408363.2015.1084990

- Ribeiro A, Igual-Perez MJ, Santos Silva E, Sokal EM. Childhood Fructoholism and Fructoholic Liver Disease. Hepatol Commun. 2018;3(1):44-51. Published 2018 Nov 30. doi:10.1002/hep4.1291

- Almeida C, Malheiro A. Sleep, immunity and shift workers: A review. Sleep Science, 2016;9(3):164-168. doi:10.1016/j.slsci.2016.10.007

- Besedovsky L, Lange T, Born J. Sleep and immune function. Pflügers Archiv – European Journal Of Physiology, 2011;463(1):121-137. doi:10.1007/s00424-011-1044-0

- Dhabhar FS. Effects of stress on immune function: the good, the bad, and the beautiful. Immunol Res. 2014;58(2-3):193–210. doi:10.1007/s12026-014-8517-0

- Çolak Y, Afzal S, Lange P, Nordestgaard BG. Smoking, Systemic Inflammation, and Airflow Limitation: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis of 98 085 Individuals From the General Population. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(8):1036-1044. doi:10.1093/ntr/nty077

- Turner J. Is immunosenescence influenced by our lifetime “dose” of exercise?. Biogerontology. 2016;17(3):581-602. doi:10.1007/s10522-016-9642-z

- Genuis SJ, Kyrillos E. The chemical disruption of human metabolism. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2017;27(7):477-500. doi:10.1080/15376516.2017.1323986

- Mitro SD, Johnson T, Zota AR. Cumulative Chemical Exposures During Pregnancy and Early Development. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2015;2(4):367-378. doi:10.1007/s40572-015-0064-x

- Wang A, Padula A, Sirota M, Woodruff TJ. Environmental influences on reproductive health: the importance of chemical exposures. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(4):905-929. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.07.1076

- Weiner ID, Mitch WE, Sands JM. Urea and Ammonia Metabolism and the Control of Renal Nitrogen Excretion. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(8):1444-1458. doi:10.2215/CJN.10311013

- Kimoloi S, Rashid K. Potential role of Plasmodium falciparum-derived ammonia in the pathogenesis of cerebral malaria. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:234. Published 2015 Jul 3. doi:10.3389/fnins.2015.00234

- Richardson AJ, McKain N, Wallace RJ. Ammonia production by human faecal bacteria, and the enumeration, isolation and characterization of bacteria capable of growth on peptides and amino acids. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:6. Published 2013 Jan 11. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-13-6

- Mancini A, Campagna F, Amodio P, Tuohy KM. Gut : liver : brain axis: the microbial challenge in the hepatic encephalopathy. Food Funct. 2018;9(3):1373-1388. doi:10.1039/c7fo01528c

- Ramachandran G. Gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial toxins in sepsis: a brief review. Virulence. 2014;5(1):213-218. doi:10.4161/viru.27024

- Akpinar-Elci M, White SK, Siegel PD, et al. Markers of upper airway inflammation associated with microbial exposure and symptoms in occupants of a water-damaged building. Am J Ind Med. 2013;56(5):522-530. doi:10.1002/ajim.22165

- Park J, Lee IS, Kim KH, Kim Y, An EJ, Jang HJ. GI inflammation Increases Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter Sglt1. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(10):2537. Published 2019 May 23. doi:10.3390/ijms20102537

- Albhaisi SAM, Bajaj JS, Sanyal AJ. Role of gut microbiota in liver disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2020;318(1):G84-G98. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00118.2019

- Bennett JW, Klich M. Mycotoxins. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16(3):497-516. doi:10.1128/cmr.16.3.497-516.2003

- Brewer JH, Thrasher JD, Hooper D. Chronic illness associated with mold and mycotoxins: is naso-sinus fungal biofilm the culprit?. Toxins (Basel). 2013;6(1):66-80. Published 2013 Dec 24. doi:10.3390/toxins6010066

- Vighi G, Marcucci F, Sensi L, Di Cara G, Frati F. Allergy and the gastrointestinal system. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;153 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):3-6.

- Quinton LJ, Walkey AJ, Mizgerd JP. Integrative Physiology of Pneumonia. Physiol Rev. 2018 Jul 1;98(3):1417-1464. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032

- Morowitz MJ, Carlisle EM, Alverdy JC. Contributions of intestinal bacteria to nutrition and metabolism in the critically ill. Surg Clin North Am. 2011;91(4):771-85, viii.

- Quigley EMM. Gut bacteria in health and disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2013;9(9):560-9.

- Mu Q, Kirby J, Reilly CM, Luo XM. Leaky Gut As a Danger Signal for Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol. 2017;8:598. Published 2017 May 23. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00598

- Hollon J, Puppa EL, Greenwald B, Goldberg E, Guerrerio A, Fasano A. Effect of gliadin on permeability of intestinal biopsy explants from celiac disease patients and patients with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Nutrients. 2015;7(3):1565-76. Published 2015 Feb 27. doi:10.3390/nu7031565

- König J, Wells J, Cani PD, et al. Human Intestinal Barrier Function in Health and Disease. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7(10):e196. Published 2016 Oct 20. doi:10.1038/ctg.2016.54

- Bischoff SC, Barbara G, Buurman W, et al. Intestinal permeability–a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:189. Published 2014 Nov 18. doi:10.1186/s12876-014-0189-7

- Szabo G, Saha B. Alcohol’s Effect on Host Defense. Alcohol Res. 2015;37(2):159-170.

- Bishehsari F, Magno E, Swanson G, et al. Alcohol and Gut-Derived Inflammation. Alcohol Res. 2017;38(2):163-171

- Rakhi NK, Tuwani R, Mukherjee J, Bagler G. Data-driven analysis of biomedical literature suggests broad-spectrum benefits of culinary herbs and spices. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0198030. Published 2018 May 29. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198030

- Vázquez-Fresno R, Rosana ARR, Sajed T, Onookome-Okome T, Wishart NA, Wishart DS. Herbs and Spices- Biomarkers of Intake Based on Human Intervention Studies – A Systematic Review. Genes Nutr. 2019;14:18. Published 2019 May 22. doi:10.1186/s12263-019-0636-8

- Bhuyan DJ, Alsherbiny MA, Perera S, et al. The Odyssey of Bioactive Compounds in Avocado (Persea americana) and Their Health Benefits. Antioxidants (Basel). 2019;8(10):426. Published 2019 Sep 24. doi:10.3390/antiox8100426

- Garbossa SG, Folli F. Vitamin D, sub-inflammation and insulin resistance. A window on a potential role for the interaction between bone and glucose metabolism. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017;18(2):243-258. doi:10.1007/s11154-017-9423-2

- Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline [published correction appears in J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Dec;96(12):3908]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1911-1930. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-0385

- Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(1):53-58. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-2704

- Cesareo R, Attanasio R, Caputo M, et al. Italian Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AME) and Italian Chapter of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) Position Statement: Clinical Management of Vitamin D Deficiency in Adults. Nutrients. 2018;10(5):546. Published 2018 Apr 27. doi:10.3390/nu10050546